Let's Take This Offline (Or My Bookshelf)

We had a lot of books. So many books that our first purchase together was a bookshelf. And still, they wouldn’t all fit, so we had to say our goodbyes to some. Where Aarti and I had two copies of the same book, things were easy, but this only applied to our taste in fiction.

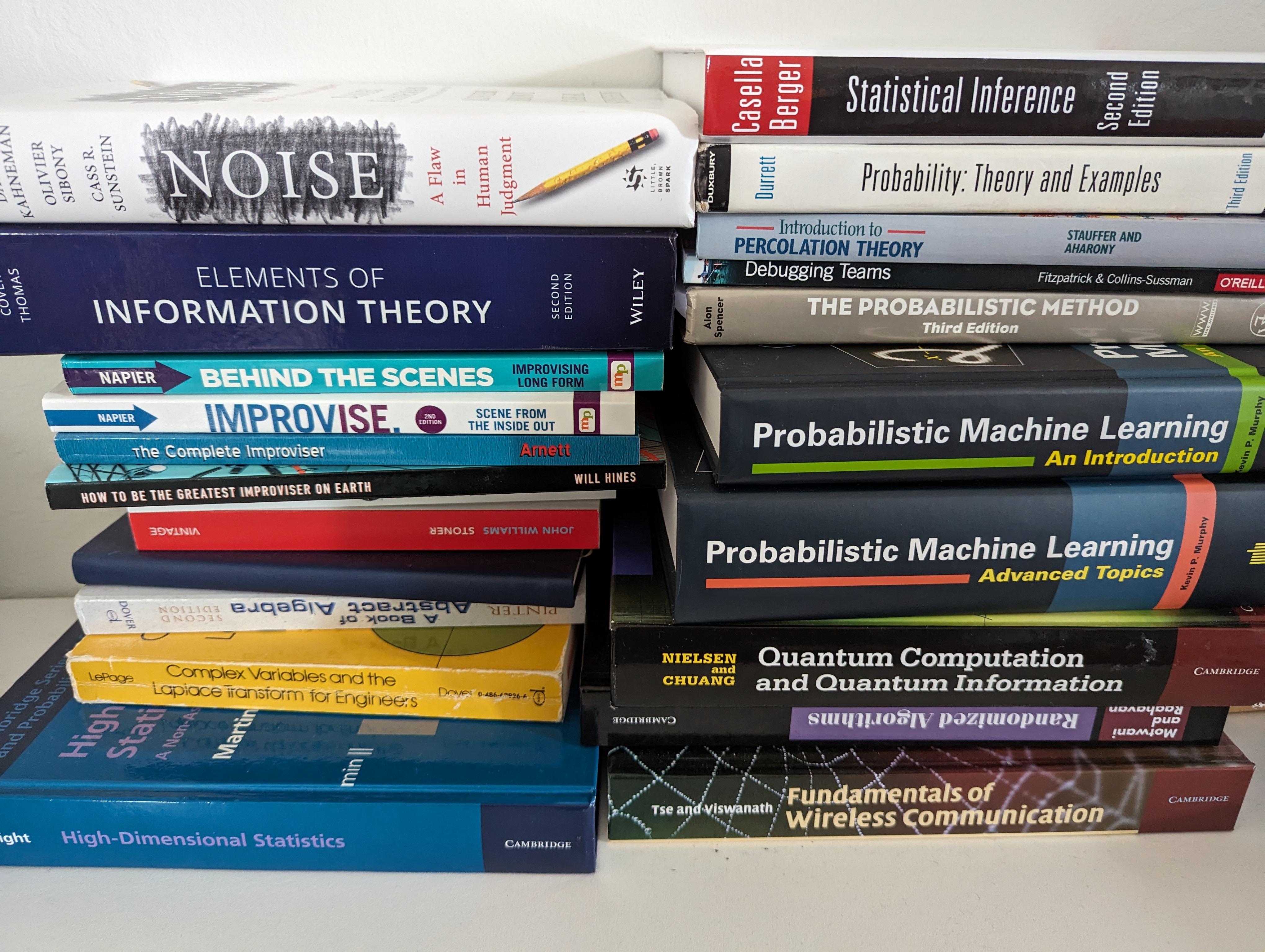

When it came to non-fiction, most of my books were from grad school, and a decade had passed since I’d graduated. I had started managing double-digit sized teams at that point and asked myself how much I’d realistically be able to stay technical. This was also around the time that Marie Kondo had reached peek popularity, and I took a hard look at my bookshelf to determine what still sparked joy. I kept Durrett’s Probability: Theory and Examples while saying goodbye to Billingsley’s Probability and Measure. Yes to Feller (volumes I and II). No to Emanuel Parzen’s Stochastic Processes. Goodbye Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. Goodbye, Gallager’s Information Theory and Reliable Communication. I’ll miss you most of all.

This was at the start of a pandemic. Places closed. Then they opened again with some restrictions. We started leaving the house again. We stepped into a nearby bookstore. As I walked to the math and science section, I was surprised by the lack of Dover or Springer books. In their place were popular math and science books. I went to other bookstores and noticed the same pattern. Occassionally, there would be a stray Dover at a used bookstore or a Six Not So Easy Pieces, but by and large bookstores had konmaried these books out.

I searched online. Some of the books I had given away were out of print. I felt a sense of loss, so I tried to find a constructive way to cope. Yes, I went on a book shopping spree. This was around the time that text to imeage models were becoming popular, and I was playing around with stable diffusion to create AI art, so I leaned into getting back some probability and statistics books including some new ones focused on machine learning. Welcome back, Casella and Berger. It’s been too long, Noga Alon.

My favorite addition to the shelf has been Kevin P. Murphy’s two-volume Probabilistic Machine Learning. It’s a tour de force through so many of the algorithms and approaches surrounding both what we experience in our software today, grounded in explanations that should be accessible to anyone with a solid foundation in probability theory and statistics. It’s the one I find myself picking up the most often, flipping to random pages based on something I had thought about on that given day. And it’s made me feel more connected technically to the work that is happening on the teams I manage as well as the broader research community. It sparks joy.